Federal Primary Law

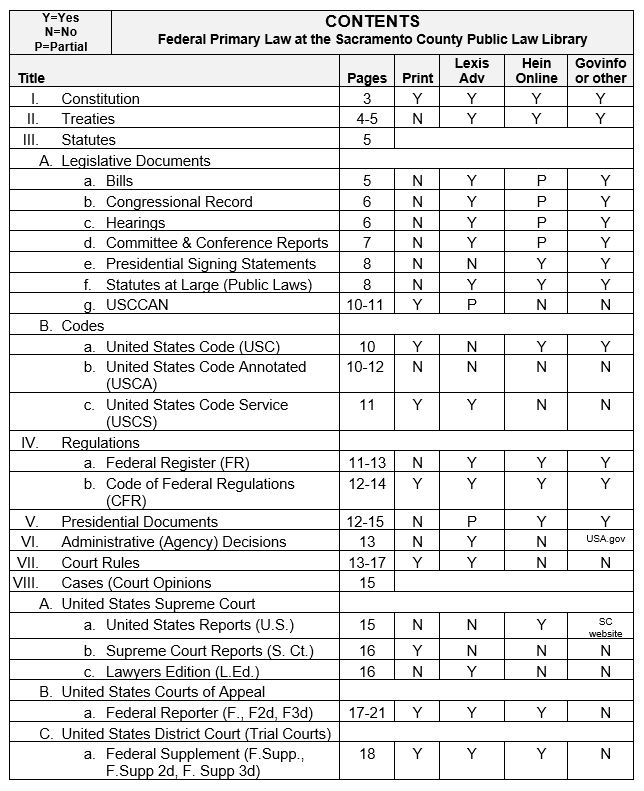

This guide details the major sources of primary federal law, and how to access them at the Sacramento County Public Law Library.

Legal research materials are generally classified as being either primary or secondary sources. Primary sources are “the law” itself, which we are bound to follow. Secondary sources are materials about the law; they explain and help us to find “the law” in a given situation. Although secondary sources, sometimes called “persuasive authority,” are very useful in legal research, and courts often consider them, no one is legally bound by them.

An example of federal primary law is the United States Code. This multi-volume set contains the United States’ statutes, codified (organized by subject) into 54 titles. An example of a secondary source is Nimmer on Copyright, a critical examination of copyright law. While Nimmer’s analysis is highly regarded and often cited by courts, it is not “the law.”

Related Guides:

- Reading Citations

- California Primary Law

- Lexis Advance Shepard’s®

- West Digests

- California Legislative History

Basics

The purpose of this guide is to identify all of the federal primary law resources in the Law Library’s collection. Because the Sacramento County Public Law Library is a California-focused, practice-oriented library, our selection of federal primary material in print is minimal. The bulk of our federal primary law collection is available electronically through subscription databases, accessible in the Law Library only.

Much of federal primary law is available on the free internet site, GovInfo. GovInfo is provided by the Government Printing Office. It provides authentic, digitally signed PDF files of federal government publications, and is freely accessible from almost anywhere.

Primary law includes materials such as the Constitution, statutes, legislative documents, court opinions (cases), rules of court, administrative decisions, and regulations. The Law Library has the majority of these online in Lexis Advance or HeinOnline, which may only be used in the Law Library.

Lexis Advance is organized by content type and jurisdiction. Start from the Home Page at the “Explore Content” section, and click on the [Federal] tab. To start your search, click on the source material you want to search, for example, [CFR-Code of Federal Regulations] and then enter keyword(s) or a citation in the red search box and click on the red magnifying glass. Additional federal resources may be found by selecting the “Content Type” tab and clicking on the resource types listed such as “cases,” “statutes and legislation,” or related headings, and then selecting the heading [Federal].

HeinOnline provides scanned pages of original material. The material is arranged in “Collections.” From the Home Page, click on the Collection that you need, for example, “Federal Register Library,” drill down to the specific publication you need, and either click on the title to browse, or enter a citation in the drop-down box. If you have a specific citation, click the “Citation” tab in the search box at the top of the page and select the “Citation Navigator” link to put the citation in the correct format.

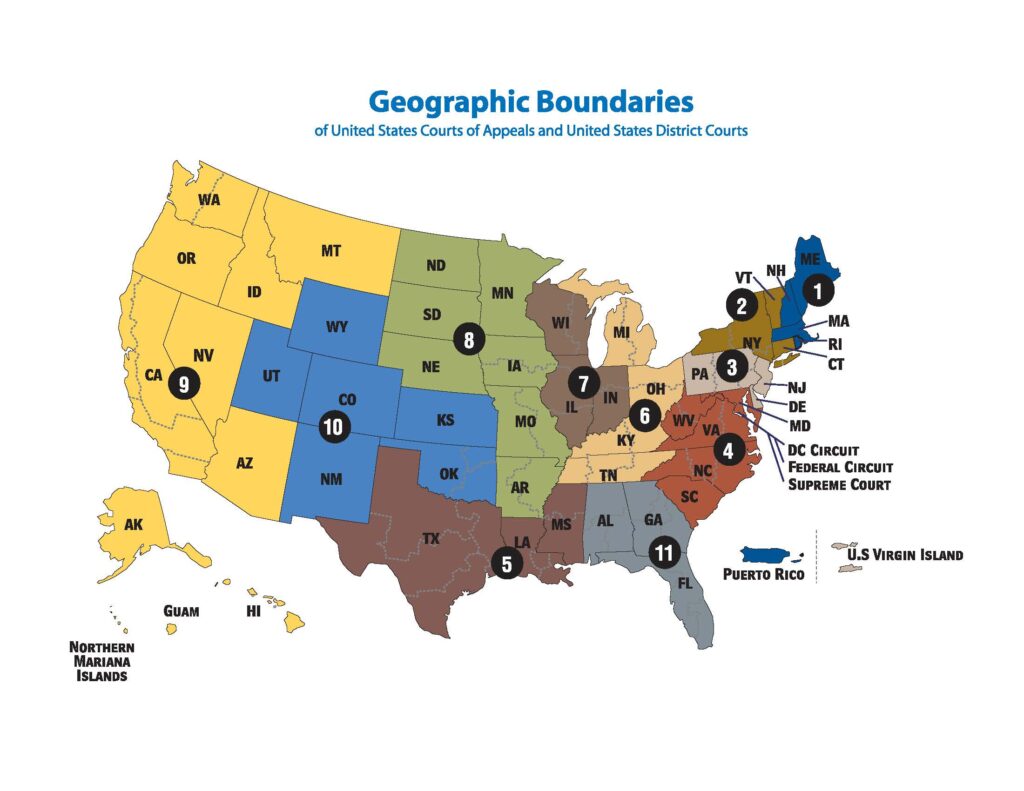

An understanding of the federal court system is helpful when researching federal case law. A map is provided below. There are 13 appellate courts that sit below the U.S. Supreme Court, and they are called the U.S. Courts of Appeals. The 94 federal judicial districts are organized into 12 regional circuits, each of which has a court of appeals. The nation’s 94 district or trial courts are called U.S. District Courts. Resources for searching case law begin on page sixteen of this guide.

Source: United States Court: “Court Role and Structure”

Resources for locating Federal primary law in the Law Library

United States Constitution

Our Founding Fathers convened at what is now called Independence Hall in Philadelphia in May of 1787 to revise the Articles of Confederation, our first “constitution.” After much disagreement and debate, it became clear that, rather than an amendment of the existing Articles, an entirely new structure of government would need to be created. All through that summer, the delegates drafted and redrafted the articles of the new Constitution, which was formally signed on September 17, 1787.

During the debates on its adoption, opponents of the new Constitution repeatedly demanded a “bill of rights” that would spell out the limits of federal government power over the individual. In September 1789, the United States’ First Congress therefore proposed twelve amendments. The first ten ratified by three-fourths of the state legislatures now comprise the first ten amendments of the Constitution, known as the Bill of Rights.

According to Article VI, Clause 2, the Supremacy Clause, the Constitution, U.S. Treaties, and laws made pursuant to the U.S. Constitution, shall be “the supreme law of the land.”

The Constitution, Articles of Confederation, and Declaration of Independence can be found in Volume 1 of the United States Code.

LexisAdvance: In the [Explore Content] section 🡪 Select [Statutes and Legislation] 🡪 Under the Content Type heading, select [Constitutions] 🡪 Under the Federal Heading, select [USCS – Constitution of the United States].

This file contains the current Constitution of the United States from the United States Code Service (USCS).

HeinOnline: Select [U.S. Code] 🡪 Select [United States Code] 🡪 Select [2018 edition] 🡪 Select [v. 1 Titles 1-5] 🡪 Select p.XLV [Organic Laws of the United States]

In addition, an excellent book, The Constitution of the United States of America: Analysis and Interpretation: Annotations of Cases Decided by the Supreme Court of the United States to June 28, 2012, prepared by the Congressional Research Service of the Library of Congress, is kept behind the Reference Desk at KF 4527 .U54. Ask the Reference Librarian to see this volume.

govinfo.gov: The current (2022) edition of The Constitution of the United States of America: Analysis and Interpretation is also available on govinfo.

Treaties

Next to the Constitution, treaties are the “supreme law of the land,” and take precedence over statutes or any other law. Since 1945, treaties to which the United States is a party have been officially published as individual pamphlets as Treaties and Other International Acts Series (TIAS) (1996-current available in an electronic-only format from the State Department’s website.) From 1950-1984, these treaties were then published in bound volumes called United States Treaties and Other International Agreements (UST). Prior to the inception of TIAS, treaties and other international agreements were published in Treaty Series (1795-1945), Executive Agreement Series (1928-1945), and in Statutes at Large (until 1948). Texts of treaties as submitted to the U.S. Senate for ratification by the President of the United States are also published in Senate Treaty Documents (formerly known as Senate Executive Documents).

TIAS and UST often ran 5-10 years behind, making it difficult for researchers to find recent treaties. To fill this gap, private publishers began printing compilations of US treaties. There are several well-known, unofficial treaty publications produced, including:

- Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States of America (“Bevans”) (1776-1949)

- KAV Agreements (KAV) (1987-2011)

- International Legal Materials (ILM) (1962-2011)

- Treaties, Conventions, International Acts, Protocols and Agreements (“Malloy”) (1776-1937)

- Treaties and Other International Acts of the United States of America (“Miller”) (1776-1863)

- Indian Affairs, Laws and Treaties (“Kappler”) (1902-1971)

HeinOnline: Select [U.S. Treaties and Agreements Library]

Contains PDF versions of the treaty sources listed above, as well as a large number of other treaty resources, indices, and finding aids.

Lexis Advance: In the “Explore Content” section 🡪 Select [Statutes and Legislation] 🡪 Select [Treaties] 🡪 Select either [US Treaties in Lexis] or [US Treaties in Force]

[US Treaties in Lexis] is a compilation of full-text ratified and unratified treaties and international agreements, where the United States is a party or signatory from 1776 through current. (Note from vendor: Documents from Volume 31, Part 2 of the UST reporter are not included in this collection. They will be added at a later date.)

[US Treaties in Force] (as published by the GPO) contains Bilateral Treaties as of January 1, 2019; and Multilateral Agreements as of January 1, 2019.

govinfo.gov: The Congressional Documents collection includes Senate Treaty Documents.

Statutes

Legislative History Documents

Black’s Law Dictionary defines legislative history as “the background and events leading to the enactment of a statute, including hearings, committee reports, and floor debates.” Black’s Law Dictionary, 10th Ed. (2014). Researchers review the documents produced in conjunction with the legislative history of a particular statute in hopes of finding something that will aid in interpreting that statute.

One source of background information for the enactment of federal statutes is the U.S. Congressional Serial Set, commonly referred to as the Serial Set, contains the House and Senate Documents and the House and Senate Reports bound by session of Congress from July 11, 1777 through present. The Law Library doesn’t have this resource in print. However it is available on Lexis Advance and is gradually being made available on govinfo.

Lexis Advance: In the “Explore Content” section 🡪 Select [Statutes and Legislation] 🡪 Select [Legislative Histories]. Under the Federal heading, select [Congressional Documents 1777-present (U.S. Serial Set)].

Currently contains 15th-39th (1817-1867), 42nd (1871-1873), 69th (1925-1927), and the 82nd (1951-1952) Congresses.

govinfo.gov also contains the Congressional Serial Set.

For an excellent guide to conducting legislative history research, see Policy and Legislative Research for Congressional Staff: Finding Documents, Analysis, News, and Training, published by the Congressional Research Service.

Bills

A bill is a legislative proposal before Congress. Bills from each house are assigned a number in the order in which they are introduced, starting at the beginning of each Congress. Bills introduced in the Senate are preceded by “S.”; those in the House by “H.R.” (e.g., S. 49, H.R. 56). A new Congress convenes every two years, in the January following a November congressional election. Congresses have been numbered consecutively since the first, beginning in 1789. Each Congress meets in two annual “sessions,” the first in its first calendar year and the second in its second calendar year. Thus, the first session of the 117th Congress began in 2021, and the second will begin in 2022.

LexisAdvance: In the “Explore Content” section 🡪 Select [Statutes and Legislation] 🡪 Select [Federal] 🡪 Under the Bill Text heading, select [Congressional Full Text of Bills] for current session or select an archive file beginning with the [Congressional Full Text of Bills – 101st Congress, Archives].

HeinOnline: Select [U.S. Federal Legislative History Library]

Contains comprehensive federal legislative histories published by the U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO) and private publishers. Go to this library in HeinOnline and click on [LibGuide] for instructions on searching. These compilations are composed of the text of the final public law, House and Senate bill variations, congressional hearings, House and Senate reports, and more.

This library also provides access in HeinOnline to a useful finding aid derived from the well-known publication, Sources of Compiled Legislative Histories: A Bibliography of Government Documents, Periodical Articles, and Books, by Nancy P. Johnson.

govinfo: contains all published versions of bills from the 103rd Congress (1993-1994) onward in its Congressional Bills collection.

Floor Debates (Congressional Record)

Bills are introduced, debated, and voted on in each House of Congress. This is reported in the Congressional Record, the official record of the proceedings of the United States Congress, published daily while Congress is in session. Beginning publication in 1873, the Congressional Record contains four sections, the Daily Digest (index and table of contents), a House section, a Senate section, and an Extension of Remarks section, which includes tributes, statements, and other information supplementing statements made on the congressional floor. Pages are numbered sequentially in each section throughout the session of Congress, e.g., each Senate page begins with the letter S, “S1234;” each House page begins with the letter H, “H1234,” etc.

Coverage begins with the First Session of the 99th Congress (1985).

LexisAdvance: In the “Explore Content” section 🡪Select [Statutes and Legislation], then select [Congressional Record] 🡪 Select [Congressional Record]

Contains the full text chronicle of proceedings and debates in the United States Congress from 1789 to present.

govinfo: contains Congressional Record (Daily) beginning with volume 140 (1994) to current and Congressional Record (Bound), 1873 to 2016.

Hearings

A hearing is a meeting or session of a Senate, House, joint, or special committee of Congress, usually open to the public, to obtain information and opinions on proposed legislation, conduct an investigation, oversee the activities of a government agency, or evaluate the implementation of a federal law. Hearings may also be purely exploratory, providing testimony and data about topics of current interest. Whether a hearing is published depends on the committee that held the hearing.

Lexis Advance: In the [Explore Content] section 🡪 Select [Statutes and Legislation] 🡪 Select [Legislative Histories]. Under the Federal heading, select [Congressional Hearings – 1824-current].

Contains hearings from 1824 to current.

govinfo: contains select House, Senate and joint hearings from the 85th Congress (1957-1958) to current in its Congressional Hearings collection.

Committee Reports

Bills are usually referred to a committee (according to subject matter) after they are introduced. Committees often, in turn, refer the legislation to one of its subcommittees. Subcommittees may request reports from government departments, hold hearings, “markup” the bill (meet to propose changes), and “report” the bill back to the full committee. The full committee can do the same thing, with or without prior subcommittee consideration, and, by majority vote, “report” the legislation to its full chamber (i.e., the House or Senate).

When a committee reports a bill for consideration by the entire chamber, it often drafts a report on the legislation (the House requires a written report for this process; the Senate does not). These committee reports can be particularly useful in legislative history research because they often describe the purpose of the legislation and explain specific provisions. Committee reports are identified as House Report (H. Rep.) or Senate Report (S. Rep.) and assigned a number (e.g., S. Rep. 112-31 was the 31st report to the Senate in the 112th Congress).

Lexis Advance: In the “Explore Content” section 🡪 Select [Statutes and Legislation] 🡪 Select [Legislative Histories]. Under the Federal heading, select [Committee Report].

Coverage is from 1981-1982; and 1989-current (selected coverage from 1981-1982 and 1989-1992).

Conference Committee Reports

When there are differences between the House and Senate versions of a bill, the two chambers may establish a conference committee to reach agreement on a common version. Upon reaching agreement, the conference committee usually issues a report (usually printed as a House Report). The conference report may discuss the differences between the House and Senate-passed language, the reasons certain provisions were chosen over others, and provide additional information on the purpose of the legislation. If passed by both chambers in identical form, the legislation is sent to the President.

Conference committee reports are available in the same formats and sources as regular committee reports. They can also be found in the Congressional Record and in in the United States Code Congressional and Administrative News (USCCAN).

HeinOnline: does not contain a committee reports library; however, committee reports are included in the [U.S. Federal Legislative History Library].

Lexis Advance: In the “Explore Content” section 🡪 Select [Statutes and Legislation] 🡪 Select [Legislative Histories]. Under the Federal heading, select [Committee Report].

Alternatively, search the U.S. Serial Set to locate conference committee and other reports.

Lexis Advance: In the “Explore Content” section 🡪 Select [Statutes and Legislation] 🡪 Select [Legislative Histories]. Under the Federal heading, select [Congressional Documents 1777-present (U.S. Serial Set)].

The U.S. Congressional Serial Set, commonly referred to as the Serial Set, contains the House and Senate Documents and the House and Senate Reports bound by session of Congress from July 11, 1777 through present.

Provides access to all congressional committee reports, including reports on bills that did not become law, beginning with 1990. This database also contains the legislative history documents reprinted in USCCAN from 1948 through 1989, and the presidential signing statements reprinted in USCCAN beginning with 1986.

govinfo: contains committee reports in its Congressional committee material. Coverage of years varies by each committee.

Presidential Signing Statements

The President may approve a bill, veto it, or take no action. If the President signs a bill, he may issue a signing statement. If no action is taken, the legislation becomes law after ten days (excluding Sundays) unless Congress adjourns, in which case the bill does not become law (this is known as a “pocket veto”). If the President vetoes the legislation, Congress may override the veto with two-thirds of each chamber voting to do so. If Congress overrides the veto, the bill becomes law without the President’s signature.

A controversy over the President’s use of signing statements erupted during the administration of President George W. Bush, in which critics charged the unusually extensive statements modified the meaning of statutes. In July 2006, an American Bar Association task force declared that the use of signing statements to modify the meaning of duly enacted laws serves to “undermine the rule of law and our constitutional system of separation of powers.” Press Release, Blue-Ribbon Task Force Finds President Bush’s Signing Statements Undermine Separation of Powers American Bar Association Senate Vol. 152 (July 24, 2006).

Presidential signing statements may be found in the Compilation of Presidential Documents, the official publication of presidential documents. They are also printed along with the bill in United States Code Congressional and Administrative News since 1986.

Coverage begins with 1986.

HeinOnline: Select [U.S. Presidential Library].

Contains the Weekly Compilation of the Presidential Documents (1965-2009), continued as the Daily Compilation of Presidential Documents (2009-current).

govinfo: contains the Compilation of Presidential Documents from 1992 to current.

Statutes at Large (Stat)

After the President signs a bill into law, it is assigned a law number, and prepared for publication in the Statutes at Large, the official publication of the law. These are often called “Slip Laws.” Laws cited to in the Statutes at Large will have a volume number, the abbreviation “Stat.,” and the page number upon which the law begins, e.g., “105 Stat. 603.” Statutes passed prior to 1957 are identified by their Statutes at Large citation.

Since 1957, Acts of Congress related to the general public have been designated in the form “Public Law X-Y,” where X is the number of Congress and Y is the chronological number of that public act in that Congress. (Public laws affect society as a whole, while private laws affect an individual, family, or small group. Acts relating to individuals are analogously given Private Law X-Y designations.)

LexisAdvance: In the “Explore Content” section 🡪 Select [Statutes and Legislation] 🡪 Select [Federal] 🡪 Select [USCS Statutes at Large Table].

Contains the Public Laws enacted by each Congress, starting with the 1st Congress (1789), in numerical order according to their date of enactment.

HeinOnline: Select [U.S. Statutes at Large Library]

Contains vol. 1 (1789-1799) through vol. 127 (2013). A link is provided to the most recent public laws not published in the U.S. Statutes at Large.

govinfo: contains the United States Statutes at Large from the 82nd Congress (1951) to the 113th Congress, second session (2014), volumes 65-128; and Public and Private Laws from the 104th Congress (1995-1996 to current).

U.S. Code Congressional and Administrative News (USCCAN)

USCCAN, a commercial service published by West (Thomson Reuters), reprints the full text of new public laws and the major committee and conference reports for most public laws since 1941, the 1st Session of the 77th Congress.

First published monthly in soft-bound pamphlets, USCCAN contains a cumulative subject index and a cumulative Table of Laws Enacted in addition to the new public laws and selected relevant documents. The pamphlets are reissued into bound volumes after each session of Congress ends. In addition to federal laws and select committee reports, USCCAN publishes presidential proclamations, executive orders, President’s messages, federal regulations, proposed constitutional amendments, federal court rules, and sentencing guidelines, all arranged in chronological order.

When published in bound volumes, the legislative history documents are placed in separate volumes from the rest of the materials. Prior to the 99th Congress, the legislative history materials in USCCAN contained only a House or Senate report. Since the 99th Congress (1985–1986), the legislative history materials in USCCAN have included the House or Senate report, the conference committee report, and any presidential signing statements.

USCCAN is located at KF 48 .W45 (Compact).

HeinOnline: does not contain a USCCAN library, as USCCAN is a rival vendor’s product. Access to public laws, however, is available through the [U.S. Statutes at Large Library].

What is positive law codification?

Of the 54 titles, 27 have been enacted into positive law (these titles are 1, 3, 4, 5, 9, 10, 11, 13, 14, 17, 18, 23, 28, 31, 32, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 44, 46, 49, 51, and 54). When a title of the Code is enacted into positive law, the text of the title becomes legal evidence of that law. Titles that have not been enacted into positive law are only prima facie (a Latin expression meaning “at first appearance”) evidence of the law. In that case, the text of the law in the Statutes at Large still governs.

Positive law codification is the process of preparing and enacting, one title at a time, a revision and restatement of the statutes of the United States. Because many U.S. statutes are inconsistent, redundant, or obsolete, the Office of the Law Revision Counsel of the House of Representatives has been authorized to revise and codify, for enactment into positive law, each title of the Code. When its project is complete, all the titles of the Code will be legal evidence of the law and recourse to the Statutes at Large for this purpose will no longer be necessary. Positive law codification bills prepared by the Office do not change the meaning or legal effect of a statute being revised and restated. Rather, the purpose is to remove ambiguities, contradictions, and other imperfections from the law.

govinfo: Likewise, because USCCAN is a rival vendor’s product, it is not available on govinfo. However, many of the documents published in USCCAN are on govinfo, including the Statutes at Large, committee reports, the Federal Register, and various Presidential documents.

Codes

United States Code (USC)

The United States Code (USC) is the codification by subject of the laws of the United States. It is divided by broad subjects into 54 titles and published by the Office of the Law Revision Counsel of the U.S. House of Representatives. The USC is published every six years (the last edition was published in 2018), and five annual cumulative supplements (designated as Supplements I through V) are printed in intervening years.

The officially-published USC does not contain annotations (research references and editorial analysis by the publishers). For that reason, and because of its lack of currency (as of July, 2023, the most recent available edition was 2018, and a 2021 supplement), most researchers use the annotated versions created by commercial publishers, even though citation to the official USC is required by most legal style guides and court rules.

The United States Code is located at Y 1:2/5:2018 (Compact).

HeinOnline: Select [U.S. Code]

Contains the 1925 to 2018 editions of the USC, up to and including the 2021 Supplement.

govinfo: contains the United States Code beginning with the 1994 edition.

United States Code Annotated (USCA)

USCA is the annotated (includes research references and editorial analysis) version of the United States Code published by West (Thomson Reuters). In general, the language of each section of a statute is followed by “Historical Notes” indicating which public law created the code section and which have amended it over time, if any. Following that is a section of “Library References,” which contains leads for further research, such as citations to secondary sources like law review articles, treatises, and legal encyclopedia articles (likely to be published by West (Thomson Reuters)), finding aids such as digest topics and key numbers (published solely by West (Thomson Reuters)), and references to relevant Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) sections. Finally, the “Notes of Decisions” section contains very brief summaries of cases discussing the code section, followed by a citation to the case. These brief summaries of cases are commonly called “annotations.”

In general, West (Thomson Reuters)’s publishing philosophy, which applies to all of its publications, including secondary sources like the legal encyclopedia Corpus Juris Secondum (CJS), is to be comprehensive. For example, almost every case that cites to a particular code section will be included in the Notes of Decisions section of USCA, and the footnote corroborating a legal proposition in CJS will include a case from each of the 50 states.

United States Code Service (USCS)

USCS is the annotated version of the USC published by LexisNexis. It is identical in arrangement to the USCA. Although there will be some overlap, the references to other publications for further research, relevant CFR sections, and case annotations may be different, since they are selected and written by different editors. In addition, the secondary sources are more likely to be published by LexisNexis than by West (Thomson Reuters).

In general, LexisNexis’ publishing philosophy, which applies to all of its publications, including secondary sources like the legal encyclopedia American Jurisprudence (Am Jur), is to be selective. For example, only the most important cases, as determined by the USCS editors, are included in the Notes of Decisions section of USCS, and the footnotes corroborating a legal proposition in Am Jur include only the most important relevant cases, again as determined by USCS editors. Although West (Thomson Reuters) now publishes Am Jur, West has, for the most part, retained LexisNexis’ publishing philosophy.

USCS is located at KF 62 .L38 (Compact).

Lexis Advance: In the “Explore Content” section 🡪 Select [Federal] 🡪 Select [USCS-United States Code Service]. Contains the current edition of the code as published in United States Code Service (USCS).

Court Rules

Court rules prescribe procedures for practice in the courts. They dictate such matters as how to file a lawsuit, what evidence is admissible at trial, and grounds for appeal. There are rules of general applicability, which apply in all of the federal courts at a given level (e.g., the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure apply in all U.S. District Courts; the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure apply in all U.S. Circuit Courts of Appeal), and local rules that apply only in the individual courts which have adopted them (e.g., the Local Rules of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of California).

The United States Supreme Court derives the authority to create federal court rules of general applicability from the Rules Enabling Act, 28 U.S.C. §§ 2071-2077, and exercises this authority in cooperation with the Judicial Conference of the United States. The Judicial Conference’s Standing Committee on Rules of Practice and Procedure has five advisory committees (Appellate, Bankruptcy, Civil, Criminal, and Evidence) that make recommendations for rule changes to the Standing Committee. Amendments approved by the Judicial Conference at its September annual meeting are transmitted to the Supreme Court, which must approve and transmit the proposed amendments to Congress by May 1 of that year. If Congress does not pass legislation to reject, modify, or defer the rules, they take effect on December 1.

The Federal Judiciary’s rulemaking website contains the current rules of general applicability, along with pending rules amendments, proposed amendments published for public comment, records and archives of the rules committees, and a description of the rule-making process.

Each court adopts its own local rules, which can usually be found on the court’s website, e.g., Ninth Circuit Rules for the Court of Appeals.

The Law Library has:

- California Rules of Court: Federal Bankruptcy Courts, KFC 992 .A33 (Ref Desk)

- California Rules of Court: Federal District Courts, KFC 992 .A32 (Ref Desk)

- Federal Local Court Rules, KF 8820 .A2

- Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure, with Forms, KF9052 .A459 Online only.

- Federal Rules of Civil Procedure: Rules and Commentary, KF 8840 .C65

- Federal Criminal Code and Rules KF 9606 .99 .D567 (Ref Desk)

Federal rules can also be found in the Court Rules volumes at the end of the USCS. KF 62 .L38 (Compact).

LexisAdvance: In the “Explore Content” section 🡪 Select the tab [Federal] 🡪 Select [USCS — Federal Rules Annotated]. Contains the Federal Rules Annotated from the United States Code Service. These rules include:

- Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

- Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure

- Federal Rules of Evidence

- Rules of the U.S. Supreme Court

- Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure, and

- Rules of Bankruptcy Procedure and Official Bankruptcy Forms, among many others.

LexisAdvance: In the “Explore Content” section 🡪 Select the tab [State] 🡪 Select [California] 🡪Under the Statutes & Legislation heading, select [CA-California Local, State & Federal Court Rules]

Contains local rules for the all federal District and Bankruptcy courts located in California.

Cases (Court Opinions)

Federal courts are required by statute (28 U.S.C § 411) and court rule (United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit Rules 36.1; 36.2) to publish their decisions. Cases are published in “reporters,” a series of volumes in which cases appear roughly in the order in which they were decided. A reporter may carry the cases of a single court or of several related courts. Case citations generally include the last names of the first-named parties, the volume number of the reporter in which the case can be found, an abbreviation for the reporter in which the case can be found, the page number upon which the case begins, and the year the case was decided. For example, Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. 137 (1803), decided by the United States Supreme Court in 1803, can be found in volume 5 of the United States Reports beginning on page 137. If the court that decided the case cannot be determined from the reporter abbreviation, that information is included in the parenthetical with the year. For example, only United States Supreme Court decisions appear in the United States Reporter (abbreviated “U.S.”), but because the Federal Reporter contains decisions from all thirteen federal appellate courts, the case of Perry v. Brown, decided by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in 2012 and appearing on page 1052 of volume 671 of the Federal Reporter, Third Series (abbreviated “F.3d”), is cited as Perry v. Brown, 671 F.3d 1052 (9th Cir. 2012).

United States Supreme Court

When Congress first met on March 4, 1789, one of the first items of business was to fulfill the requirements of Article III, section 1, of the Constitution, which provides that the “judicial power of the United States, shall be vested in one Supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish.” The First Congress responded by enacting the Judiciary Act of 1789, which established thirteen district courts in major cities, three circuit courts, and a Supreme Court comprised of a Chief Justice and five Associate Justices.

Today the United States Supreme Court consists of the Chief Justice and eight Associate Justices. At its discretion, and within certain guidelines established by Congress, the Supreme Court hears only a limited number of the cases it is asked to decide each year. Those cases may begin in the federal or state courts, and they usually involve important questions about the Constitution or federal law. All federal courts are courts of limited jurisdiction; that is, they can only hear cases that Congress has decided they can hear, e.g., between citizens of different states where the amount in controversy is over $75,000 (28 U.S.C. § 1332) (called “diversity jurisdiction”) or where a question arises under the Constitution, laws, or treaties of the United States (28 U.S.C. § 1331) (called “federal question jurisdiction”).

United States Supreme Court decisions are currently published in three main reporters: the United States Reports (abbreviated U.S.), the Supreme Court Reporter (abbreviated S.Ct.), and the United States Supreme Court Reports, Lawyers Edition (abbreviated L.Ed.). Often two, or even all three, citations are listed, e.g., Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. 137, 2 L. Ed. 60 (1803) (Marbury v. Madison does not appear in the Supreme Court Reporter because the Supreme Court Reporter did not begin publication until 1883. Marbury v. Madison does appear in Westlaw, however, at 1803 WL 893 (U.S.Dist.Col.)). The additional citations are called parallel citations.

United States Reports (U.S.)

All United States Supreme Court opinions are published. The United States Reports is the official government publication of Supreme Court opinions. Published by Government Printing Office (GPO), “slip” (unbound) opinions appear about eight months from date of decision; “advance sheets” (temporary soft-bound volumes) about two years from date of decision; and permanent, bound volumes about two years after the advance sheets. The U.S. Supreme Court provides access to the United States Reports (supremecourt.gov) (Vol. 502 et seq.), including all of the opinions, orders, and other materials issued for the Court’s 1991 Term and subsequent years. The Supreme Court also provides free access to its Slip Opinions (2012-current).

The Library of Congress provides access to the United States Reports (Library of Congress), including late Colonial material, from 1754-2012.

In addition to the text of the opinion(s) the United States Reports contains a synopsis of the case written by the official Supreme Court Reporter of Decisions. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U.S. 321, 337, 26 S.Ct. 282, 50 L.Ed. 499 (1906).

Until the late 19th century, there was no such thing as an “official” reporter in the United States; indeed, the first 90 volumes (1790-1874) of the United States Reports were originally published as “nominative” reporters, named after the person who compiled or published the reports: Dallas, Cranch, Peters, Howard, Black, and Wallace. Dallas’ first volume (1 Dall.) also contained Pennsylvania state cases. The United States Reports began publication in 1875; the GPO later republished all the nominative reporters and incorporated them into the United States Reports. These early United States Reports volumes are often cited with the nominative reporter volume included, e.g., “Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137 (1803).”

HeinOnline: Select [U.S. Supreme Court Library]

Contains volumes 1 through 574 (1754-2015) of the United States Reports, volumes 535 through 578 part 1 (2002-2016) of the Preliminary Prints (advance sheets), and Slip Opinions from 2002-to date.

Supreme Court Reporter (S.Ct.)

The Supreme Court Reporter is published by West (Thomson Reuters). The Supreme Court Reporter is very current; advance sheets may be as current as two weeks. In addition to the text of the opinions, each volume of the Supreme Court Reporter contains tables of cases reported and statutes construed and a table of words and phrases judicially defined. In addition to the synopsis written by the Supreme Court Reporter of Decisions, each case in the Supreme Court Reporter has a synopsis and headnote(s) written by a West (Thomson Reuters) attorney-editor, with subject access to the headnotes provided in the U.S. Supreme Court Digest. For more information on the U.S. Supreme Court Digest, see our guide, Locating Cases with a West Digest.

The Supreme Court Reporter is located at KF 101 .W47 (Compact).

United States Supreme Court Reports, Lawyers Edition (L.Ed.)

The United States Supreme Court Reports, Lawyers’ Edition began in 1958 and is now published by LexisNexis editors. The currency of the print Lawyers’ Edition is comparable to West (Thomson Reuters)’s Supreme Court Reporter. In addition to the text of the opinions and synopsis written by the Supreme Court Reporter of Decisions, each reported case includes the briefs of counsel, and contains a unique syllabus and headnotes written by LexisNexis editors, in addition to cross-references to subjects in other Lawyers Co-op publications, such as the Annotations in American Law Reports.

The California State Library, located several blocks away from the Sacramento County Public Law Library at the Stanley Mosk Library and Courts Building, 914 Capitol Mall, holds this title in print.

LexisAdvance: In the “Explore Content” section 🡪 Select the tab [Federal] 🡪 Select [U.S. Supreme Court – Lawyer’s Edition]

Contains the earliest opinion dated from January 1790 through current of all Supreme Court Lawyers’ Edition cases.

United States Courts of Appeal

There are thirteen United States Courts of Appeal. The 94 U.S. judicial districts are organized into twelve regional circuits, each of which has a United States Court of Appeals. A map is provided on page 2 of this document. A court of appeals hears appeals from the district courts located within its circuit, as well as appeals from decisions of federal administrative agencies. In addition, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit has nationwide jurisdiction to hear appeals in specialized cases, such as those involving patent laws and cases decided by the Court of International Trade and the Court of Federal Claims.

Only about 20% of all United States Court of Appeals opinions are published. Each court has its own rule setting forth criteria for publishing its opinions. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals’ Criteria for Publication Rule 36-2, which is fairly typical, states:

A written, reasoned disposition shall be designated as an OPINION if it:

(a) Establishes, alters, modifies or clarifies a rule of federal law, or

(b) Calls attention to a rule of law that appears to have been generally overlooked, or

(c) Criticizes existing law, or

(d) Involves a legal or factual issue of unique interest or substantial public importance, or

(e) Is a disposition of a case in which there is a published opinion by a lower court or administrative agency, unless the panel determines that publication is unnecessary for clarifying the panel’s disposition of the case, or

(f) Is a disposition of a case following a reversal or remand by the United States Supreme Court, or

(g) Is accompanied by a separate concurring or dissenting expression, and the author of such separate expression requests publication of the disposition of the Court and the separate expression.

(Rules 36-4 and 36-5 allow for requests for publication by the public and orders for publication by a majority of the judges, respectively).

Federal Reporter (F., F.2d, F.3d)

There is no “official” publisher of United States Courts of Appeal opinions. West (Thomson Reuters), however, publishes the Federal Reporter, now in its Third Series (999 volumes comprise each series) which contains opinions from all of the United States Courts of Appeal.

Just because an opinion is published in the Federal Reporter or any other publication, however, does not mean that the opinion is “officially” published and can be cited as precedent. Each Court of Appeals has its own rule setting forth criteria for the citation of cases. Prior to 2003, those rules varied, some allowing citation to “unpublished” opinions, and others prohibiting it. In an attempt to encourage conformity among the appellate circuits, the United States Supreme Court adopted Federal Rule of Appellate Procedure 32.1, Citing Judicial Dispositions (eff. Dec. 1, 2006), which provides:

(a) Citation Permitted. A court may not prohibit or restrict the citation of federal judicial opinions, orders, judgments, or other written dispositions that have been:

(i) designated as ‘‘unpublished,’’ ‘‘not for publication,’’ ‘‘nonprecedential,’’ ‘‘not precedent,’’ or the like; and (ii) issued on or after January 1, 2007.

(b) Copies Required. If a party cites a federal judicial opinion, order, judgment, or other written disposition that is not available in a publicly accessible electronic database, the party must file and serve a copy of that opinion, order, judgment, or disposition with the brief or other paper in which it is cited.

Ten of the thirteen federal courts of appeal, the First, Second, Third, Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, Eighth, Tenth, Eleventh, and the D.C. Circuits, now allow citation to “unpublished” opinions. Those still forbidding citation are the Seventh, Ninth, and Federal Circuits. See Melissa Serfass and Jessie Wallace Burchfield, Federal and State Court Rules Governing Publication and Citation of Opinions: An Update, 6 J. App. Prac. & Process 349 (2004). The Ninth Circuit Citation of Unpublished Dispositions or Orders Rule 36-3, for example, provides:

(a) Not Precedent. Unpublished dispositions and orders of this Court are not precedent, except when relevant under the doctrine of law of the case or rules of claim preclusion or issue preclusion.

(b) Citation of Unpublished Dispositions and Orders Issued on or after January 1, 2007. Unpublished dispositions and orders of this Court issued on or after January 1, 2007 may be cited to the courts of this circuit in accordance with FRAP 32.1.

(c) Citation of Unpublished Dispositions and Orders Issued before January 1, 2007. Unpublished dispositions and orders of this Court issued before January 1, 2007 may not be cited to the courts of this circuit, except in the following circumstances. (i) They may be cited to this Court or to or by any other court in this circuit when relevant under the doctrine of law of the case or rules of claim preclusion or issue preclusion. (ii) They may be cited to this Court or by any other courts in this circuit for factual purposes, such as to show double jeopardy, sanctionable conduct, notice, entitlement to attorneys’ fees, or the existence of a related case. (iii) They may be cited to this Court in a request to publish a disposition or order made pursuant to Circuit Rule 36-4, or in a petition for panel rehearing or rehearing en banc, in order to demonstrate the existence of a conflict among opinions, dispositions, or orders.

The Federal Reporter is located at KF 105 .F43 (1st series), at KF 105 .F44 (2nd series), and at KF 105 .F45 (3rd series, through 2018) (Compact).

LexisAdvance: In the “Explore Content” section 🡪 Select [Cases] 🡪 Under the Federal Cases by Court heading, Select [U.S. Courts of Appeals]

Coverage varies by circuit, dates can be seen by selecting the “I” icon to the right of the database name. The Ninth Circuit (for California) file has the earliest opinion dated July 1855 through current.

United States District Courts (Trial Courts)

Federal Supplement (F. Supp., F. Supp. 2d, F. Supp. 3d)

There is no “official” publisher of United States trial court opinions. West (Thomson Reuters), however, publishes the Federal Supplement, now in its third series, which contains approximately 10% of all opinions of the 94 United States District Courts.

The United States District Court for the Eastern District of California’s Local Rule 133(i)(3) on Unreported, Uncodified Citations, provides:

General Requirement. If case, statutory, or regulatory authority is relied upon that has not been reported, published or codified in any of the foregoing references, and that is not available through Westlaw/Lexis, a copy of that authority shall be appended to the brief or other document in which the authority is cited.

Incarcerated Pro Se Parties. In any action wherein a party is incarcerated and appearing pro se, that party shall be served with a paper copy of the case, statutory, or regulatory authority cited by the filing party that has not been reported as set forth in (i) and (ii) above, regardless of its availability in Westlaw/Lexis. No copy of the authority available in Westlaw/Lexis shall be filed with the court.

The Federal Supplement is located at KF 105.2 .F42 (1st series), at KF 105.2 .F421 (2nd series), and at KF105.2 .F422 (3rd series) (Compact Shelving).

LexisAdvance: In the “Explore Content” section 🡪 Select [Cases] 🡪 Under the Federal Cases by Court heading, Select [Federal District Court] 🡪 Select an individual state or territory

Coverage varies by state or territory, dates can be seen by selecting the “I” icon to the right of the database name.

Regulations

Federal Register (FR)

Created in 1935 under the Federal Register Act (44 U.S.C. §§ 1505 et seq.), and enlarged and expanded under the Administrative Procedure Act (5 U.S.C. §§ 500 et seq.), the FR is the official government publication for rules (regulations), proposed rules, and notices of federal agencies and organizations, as well as executive orders and other presidential documents. Published by the Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), the FR is updated daily and is published Monday through Friday, except federal holidays.

The “Proposed Rules” section of the FR contains notices to the public of the proposed issuance of rules and regulations. This section includes advance notices of proposed rulemaking, which describe a problem or situation and the anticipated regulatory action of the agency, and seeking public response concerning the necessity for regulation and the adequacy of the agency’s anticipated regulatory action. Additionally, many agencies voluntarily publish proposed changes to procedural rules, interpretative rules, and agency policies to gather public comments. These notices give interested persons an opportunity to participate in rule making prior to the adoption of final rules.

Many proposed rules are documents that suggest changes to current agency regulations and request public comment on those suggested changes. The “Proposed Rules” section also contains documents relating to previously published proposed rules, extending the comment period, announcing a public hearing, making available supplemental information, withdrawing a proposed rule, or correcting a previously published proposed rule. Each document begins with a heading that includes the name of the issuing agency (and subagency if appropriate), the Code of Federal Regulations title and part(s) affected, and a brief description of the specific subject of the document. Instructions for filing comments and the date by which comments must be filed are provided.

LexisAdvance: In the “Explore Content” section 🡪 Select [Administrative Codes and Regulation] 🡪 [Federal] 🡪 Under the Registers heading select [Federal Register]

Coverage from March 14, 1936 through current; coverage begins with 1 FR 1.

HeinOnline: Select [Federal Register Library]

Contains vol. 1 (1936) through current and is updated daily.

govinfo: contains Federal Register volumes from 1936 to current. In addition, the National Archives website updates the Federal Register daily and provides additional finding aides.

Code of Federal Regulations (CFR)

The CFR is the codification of the general and permanent rules published in the Federal Register. The CFR is divided into 50 titles that correspond roughly to the titles in the United States Code. The CFR is updated once each calendar year, on a staggered basis: titles 1-16 on January 1; titles 17-27 on April 1; titles 28-41 on July 1, and titles 42-50 on October 1.

Each title is divided into chapters, which usually bear the name of the issuing agency. Each chapter is further subdivided into parts that cover specific regulatory areas. Large parts may be subdivided into subparts. All parts are organized in sections, and most citations to the CFR refer to material at the section level, e.g. “21 CFR 310.502 (1997).” In this citation, the title is the numeric value to the left of “CFR,” and the part is the numeric value to the right of “CFR” and preceding the period (“.”). The subpart is the numeric value to the right of the period (“.”). You may often see a subpart identified by a letter of the alphabet, e.g. “Subpart E.” “1997” is the year the text of the section was revised, and appears on the spine of the volume. The Index and Finding Aids to Code of Federal Regulations at the end of the USCS is an exceptionally good index because it identifies CFR sections, rather than subparts.

“[Reserved]” is a term used as a placeholder within the CFR. An agency uses “[Reserved]” simply to indicate that it may insert regulatory information into this location at some time in the future. Occasionally “[Reserved]” is used to indicate that a portion of the CFR was intentionally left empty and not accidentally dropped due to a printing or computer error.

Due to the update schedule of the CFR, the List of Sections Affected provides a cumulative list of CFR sections that have been changed at any time since each CFR title was last updated.

The current CFR is at KF 70 .A3 (Compact).

LexisAdvance: In the “Explore Content” section 🡪 Select [Administrative Codes & Regs] 🡪 [Federal] 🡪 Select [CFR- Code of Federal Regulations]

Contains current edition only.

HeinOnline: Select [Code of Federal Regulations]

Contains the 1938 edition through the 2022 edition.

govinfo: contains CFR annual editions from 1996 to current. An electronic edition of the CFR which is updated daily is available at the Code of Federal Regulation’s “eCFR.”

Presidential Documents

Executive Orders are signed documents, numbered consecutively, through which the President of the United States manages the operations of the federal government.

Proclamations are signed documents, numbered consecutively, through which the President of the United States communicates information on holidays, commemorations, special observances, and trade.

Administrative orders are unnumbered signed documents through which the President of the United States conducts the administrative operations of the federal government. Administrative orders include, but are not limited, to memoranda, notices, determinations, letters, and messages.

All of these documents can be found in the Federal Register, the Compilation of Presidential Documents, Presidential Signing Statements, and Title 3 of the Code of Federal Regulations.

LexisAdvance: In the “Explore Content” section 🡪 Select [Federal] 🡪 Select [Presidential Documents and Executive Orders]

Contains a variety of Presidential Documents, executive orders, proclamations, memoranda, notices, and determinations. Dates of coverage not provided publisher.

HeinOnline: Select [U.S. Presidential Library]

Contains the Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents Vols. 1-45#3 (1965-2009), the Daily Compilation of Presidential Documents (2009-2023), Title 3 of the CFR (1936-current), and other compilations of Presidential documents.

govinfo: The Compilation of Presidential Documents collection consists of the Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents and the Daily Compilation of Presidential Documents which are the official publications of materials released by the White House Press Secretary (1993-current).

Administrative (Agency) Decisions

In addition to promulgating regulations, many federal agencies serve a quasi-judicial function, investigating disputed claims, holding hearings, ascertaining facts, weighing evidence, making conclusions from the facts as a basis for their official action, and exercising discretion of a judicial nature to reach a binding decision. A dissatisfied litigant may file a petition for review of an agency decision by a Court of Appeals (or, in some cases, for example, Social Security, in a District Court rather than a Court of Appeals).

Most recent agency decisions can be found on the agency’s website. The USA.gov website provides an A-Z Index of U.S. Departments and Agencies directory of federal agencies with links to their websites.

The text or a digest of agency rulings may also be found in treatises on the subject area. For example, West’s Social Security Reporting Service, KF 3641 .5 .A1 S6 (Compact), contains Social Security Rulings from 1995 to 2019, and the CCH Standard Federal Tax Reporter, KF 6280.C6 C4, contains IRS Rulings through December 2016.

LexisAdvance: In the “Explore Content” section 🡪 Select [Administrative and Agency Materials] 🡪 [Federal]

Select the agency to search its decisions. Coverage varies by agency.

This material is intended as general information only. Your case may have factors requiring different procedures or forms. The information and instructions are provided for use in the Sacramento County Superior Court. Please keep in mind that each court may have different requirements. If you need further assistance consult a lawyer.